US Cuts Imperil Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Effort

Maina Modu, an immunization officer in Nigeria’s northeastern Borno state, lost his wife, Hauwa, to cervical cancer in 2011. She was one of the 349,000 women globally who die from the preventable cancer every year. Thirteen years later, he jumped at the chance to protect his family and community from undergoing such loss again.

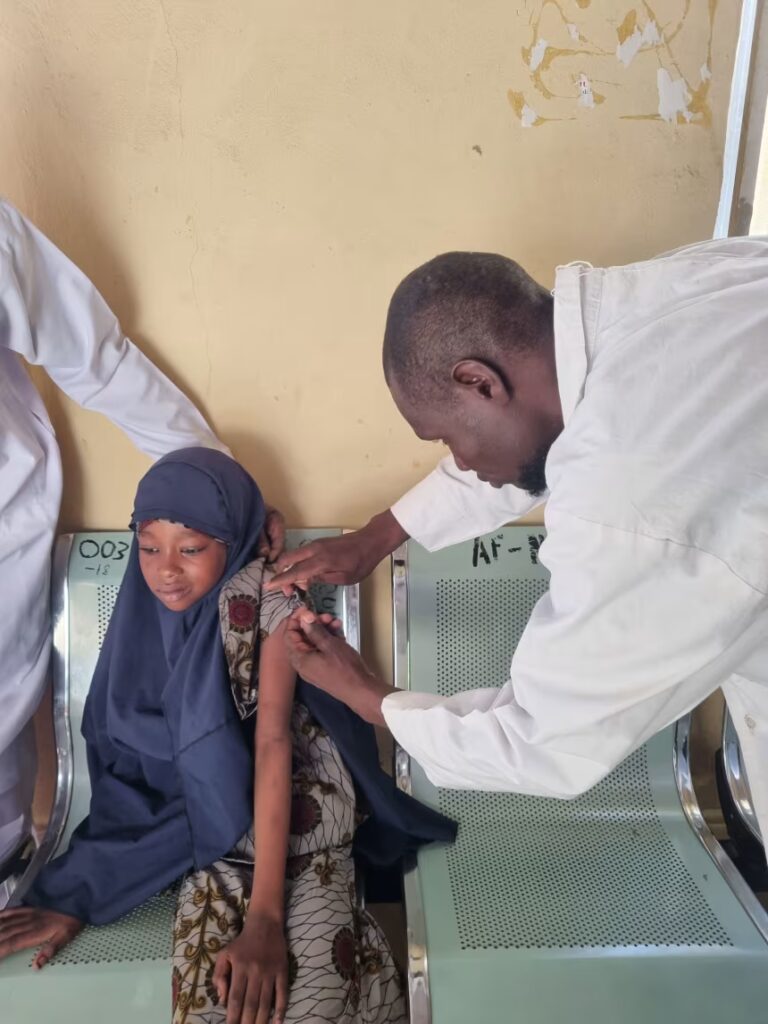

In May 2024, Modu helped launch Borno’s first immunization campaign to vaccinate adolescent girls against human papillomavirus (HPV), the pathogen that causes nearly all cervical cancers. And he made sure two of his daughters, including the youngest child of his late wife, were among the first to be protected.

“More than any other person, I was so excited when I heard about the vaccine,” said Modu, who has 10 children.

“I was so happy that they were safe,” he said. “It reminds me of the lost glory of my wife.”

His daughters were among 86 million girls vaccinated as part of a campaign led by Gavi, a public-private partnership that works with government health systems in lower-income countries to protect children and adolescents against more than 20 infectious diseases. Seventy-three million of those girls were vaccinated in just the past three years, most of them in Africa and Asia.

Its HPV vaccination program is a key piece of the World Health Organization’s global strategy to put cervical cancer on a path to elimination, following diseases like measles, polio and smallpox. But the pace of its progress against HPV and cervical cancer is now under threat after unexpected funding cuts by the US government.

Gavi set an ambitious target to dramatically scale up its HPV vaccine program in 2023. On Monday, the organization announced that it had met its goals.

“Thanks to incredible commitment from countries, partners, civil society and communities, we have now reached that target ahead of schedule,” said Dr. Sania Nishtar, Gavi’s CEO. “This collaborative effort is driving major global progress towards eliminating one of the deadliest diseases affecting women.”

But the celebration is taking place under a heavy shadow. In June, US Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. stunned health officials when, in a video address to world leaders gathered to pledge funding to Gavi, he said the US was pulling all financial support until the organization could “re-earn the public’s trust.”

Kennedy, a longtime anti-vaccine activist who has repeatedly targeted the US vaccine system since taking office, praised Gavi’s commitment to “making medicine affordable to all the world’s people” but criticized its messaging about vaccines during the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as Gavi’s handling of vaccine safety issues.

Gavi issued a detailed statement in response to Kennedy’s claims, defending its commitment to children’s health and use of independent WHO experts, noting that it “remains committed to continuing an evidence-based and scientific approach to its work and investment decisions, as it always has done.” It has continued to engage with the US government on restoring funding in the months since, a spokesperson said.

Gavi’s budget comes from national governments and private funders, including philanthropies, corporations and individual donors, with the US having been – until recently – one of its largest supporters. Since its founding in 2000, the organization has helped immunize over 1.2 billion children in 78 lower-income countries, efforts that have prevented an estimated 20.6 million deaths.

No country had ever withdrawn a financial commitment to Gavi, according to the organization. The US provided about 13% of its funding. If that isn’t restored, combined with other reduced pledges, Gavi will be left with a nearly $3 billion shortfall – approximately a quarter of its expected budget. That could force a significant scaling back of the anti-cancer campaign when Gavi’s board meets next month.

HPV vaccination remains a top priority for Gavi, a spokesperson said, but financial pressure might affect how it expands coverage. “Difficult decisions will need to be made on deploying resources to areas of highest health impact.”

In response to questions about its stance on Gavi, HHS referred to its statement issued when Kennedy announced the pause in funding, which said “the concern is that when vaccine safety issues have come before GAVI, it has treated them not as a patient health problem, but as a public relations problem.”

The agency did not address questions about what specifically Gavi can do to re-earn public trust in the eyes of the US government.

The millions of HPV vaccines Gavi has given will save lives, said Dr. Robert Bednarczyk, an associate professor of global health at the Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. “But there’s going to be new children and adolescents that are going to be eligible to get vaccinated every year. And having cuts to Gavi’s support is potentially going to reduce the access to vaccines in these settings.”

A cancer-preventing vaccine

HPV vaccines protect against a family of viruses that cause 4% of cancers globally, the most common of which is cervical cancer, the fourth deadliest cancer for women. Depending on the formulation of the vaccine, they prevent infections that cause between 70% and 90% of all cervical cancer cases.

“It’s a remarkable vaccine,” said Dr. Jessica Kahn, professor of pediatrics and senior associate dean of clinical and translational research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who noted that it also prevents infections that cause anal, vaginal, vulvar, and head and neck cancers. “It has the potential to have a truly transformative impact on cancers around the world.”

Introduced in 2006, the vaccine is only the second widely used vaccine that prevents cancer; the other prevents hepatitis B infections, a major cause of liver cancer. The HPV vaccine is typically given before the beginning of sexual activity, generally recommended for girls ages 9 to 14 in a two- or three-dose regimen. Its dramatic impact is becoming more obvious as the first women to receive the vaccine reach their 30s, 40s and 50s, when cervical cancer typically appears.

“The HPV vaccine is probably one of the most effective vaccines that we have out there, and we’re constantly getting new data in on that, as the vaccine has been used for a longer period of time,” said Bednarczyk, who studies HPV vaccination. “The research really shows us that we have a very, very good tool for reducing the amount of cervical cancer and really decreasing that burden globally.”

For years, HPV vaccines were mostly available in wealthier countries. In 2022, WHO issued guidance that a single dose of the vaccine confers effective protection, helping reduce the cost and simplify the vaccination process. Gavi/Latitude Space Africa

But for years, the vaccine was mostly available in wealthy countries, such as the United States and European nations. Further decreasing the cervical cancer burden means vaccinating school-age girls in places where cases and deaths are highest: low- and middle-income countries, the majority of them in sub-Saharan Africa. That requires a lot of investment, Bednarczyk says. “HPV vaccines are some of the more expensive vaccines that we have out there. That’s really where Gavi comes in.”

In the 2010s, Gavi began piloting school-based vaccination programs. But demand soon outpaced HPV vaccine supply, leading to shortages. The organization spent years negotiating purchasing agreements with vaccine manufacturers on behalf of the 57 lower-income countries it supports.

All the pieces were in place at the end of 2022, when a big opportunity arose to reduce cost and simplify the HPV vaccination process: WHO issued guidance that said a single dose of the vaccine confers effective protection. Gavi was ready, said Emily Kobayashi, head of Gavi’s HPV Vaccines Programme.

“That single-dose recommendation from WHO, based on the building evidence, meant that the supply we had could go much further,” she said. “And it was easier to deliver the vaccine to girls once, rather than having to track them down and give them their second or third dose.”

Gavi quickly directed $600 million to the “revitalisation” of its HPV vaccination program, supporting countries on vaccine acquisition, investments in health systems to improve HPV vaccine delivery, and integrating HPV vaccination into routine immunisation. In 2023 alone, it helped vaccinate 14 million girls – more than in the previous eight years combined.

‘Game-changer’

Nigeria, Modu’s home, was one of the first countries to launch a single-dose HPV immunization program with Gavi. The most populous country in Africa, Nigeria has a cervical cancer rate that’s four times higher than in the US.

“I was amazed when the federal government announced the introduction of HPV into immunization,” Modu said. “I mobilized my community together – my family and everybody to receive this vaccination.”

Since 2023, the country has immunized more than 13 million girls, the largest share of Gavi’s 86 million total. Nigeria is among 49 countries that have introduced HPV vaccination with Gavi support. Another seven are on track to launch programs before mid-2026, according to the organization, some of them before the end of 2025.

Maina Modu, shown with his daughters, said he mobilized everyone in his community to get HPV vaccines to people who need them. Courtesy Maina Modu

By January, Gavi estimates that HPV vaccines will be available in countries that have 89% of the world’s cervical cancer burden, up from 10% a decade ago.

“This is definitely a game-changer for HPV vaccination and access to the HPV vaccine,” Kobayashi said. “Cervical cancer is one of the most painful and undignified ways to die, and it’s almost completely preventable by one shot in childhood. … It’s going from a vaccine that’s only available in a small number of places to something that’s widely available, including in lower-income countries.”

Gavi’s current plans call for more than doubling the number of girls it has vaccinated against HPV in the next five years and continuing to expand access to more countries with high rates of cervical cancer. The goal is to vaccinate 120 million girls from 2026 to 2030. The organization spent the past year appealing to donors to fully fund its campaign to do so, which it estimates would save 1.5 million lives.

Paused

But in the wake of Kennedy’s stunning announcement, these ambitious goals are now in question.

Gavi plans its work on five-year cycles, securing pledges from its major funders in advance. Since the organization was founded, the US has been among the largest funders, exceeded only by the United Kingdom and the Gates Foundation. During the Biden administration, it pledged $1.58 billion to Gavi for 2025-30, what was set to be its largest contribution yet.

US commitments to Gavi were uninterrupted during the first Trump administration, with Trump recommitting the US pledge in 2020, but things were different almost immediately when the new administration began this year. Funding for Gavi was abruptly paused during the dismantling of the US Agency for International Development and remains in limbo.

“We continue to engage with the U.S. and hope we can sustain the strong partnership that has endured since Gavi’s founding,” the Gavi spokesperson said. “While we have incredible bipartisan support in Congress and across U.S. Administrations, including President Trump’s robust pledge at the 2020 replenishment, this is the first time we’ve seen a committed pledge walked back.”

Although the executive branch makes the country’s financial pledges to the organization, it’s Congress that sets the annual funding level to be distributed to Gavi. For the 2026 fiscal year, a House committee approved $300 million for Gavi, while its Senate counterpart has not yet released a State and Foreign appropriations bill. Meanwhile, Gavi has not received the $300 million Congress appropriated in the 2025 fiscal year, which ended in September.

In a response to questions about who would make the ultimate decision about releasing allocated funds, a State Department spokesperson said in an email, “The U.S. government speaks with one voice for all America First foreign policy programming,” adding that “The State Department collaborates closely with [other agencies] to implement assistance consistent with Trump Administration priorities. … The State Department has notified Gavi that the American taxpayer’s money must deliver better on the United States’ global health goals.”

Kennedy’s announcement came on the heels of other Trump administration shakeups pulling back from global health initiatives, including withdrawing from WHO and dismantling the US Agency for International Development.

As those shakeups reverberated across the global health field, Gavi saw other funders partially scale back expected contributions. And vaccine experts worry that US actions will not just limit budgets but erode trust in vaccines as well.

Workers provide HPV vaccines to schoolchildren in Zambia. WHO has a goal target of vaccinating 90% of girls under 15 against HPV by 2030, along with screening and treatment targets for adult women. Peter Caton/GAVI

Kennedy’s long history of criticizing vaccine programs – often with false and misleading claims – includes helping organize a lawsuit against the makers of Gardasil, the first HPV vaccine, alleging that drugmaker Merck overstated its safety (Merck has previously said the litigation has no merit). The potential fees Kennedy would collect from the case while in office became a point of contention in his confirmation hearing, before he ultimately said he would divest from the case. The next month, the parties agreed to postpone the case until February 2026.

In a separate legal action in March, a federal judge ruled in Merck’s favor, dismissing more than 200 cases that similarly challenged the safety of the vaccine.

“There are headwinds there because of vaccine disinformation and misinformation,” said Kahn, who has served on the WHO HPV Vaccine Advisory Committee and has been studying HPV vaccine effectiveness since 2006. “But this is one of the safest vaccines ever tested,” she said, citing more than 100 safety studies of 2.5 million people in six countries, which have shown no serious side effects of HPV vaccination beyond the rare allergic reactions typical for all vaccines.

“If we wanted to eliminate cervical cancer globally, we could,” said Kahn, who considers the WHO cervical cancer goals ambitious but “achievable with the right political will.”

Those goals set a target of 90% of girls under 15 vaccinated against HPV by 2030, along with screening and treatment targets for adult women.

“We’ve got these tools, we’ve got these systems to be able to prevent these cancers, but we actually need to be able to use them. And to use them, we need these concerted efforts to make sure that there is good and equitable access to these vaccines,” Bednarczyk said. “So all of these missed opportunities that we have today due to these funding cuts are potentially leaving generations of individuals more susceptible to these cancers.”

A few countries, including the Netherlands, Brazil and Hungary, have increased financial commitments to Gavi in recent months, and the organization expects to announce several others by the end of the year. But those contributions so far total less than $200 million of the nearly $3 billion budget hole. Gavi’s leadership will be making decisions on how to use the funding it does have at a board meeting in December and finalizing them by the summer.

“Our leadership and Board are looking at ways in which cuts can be applied to Gavi programmes while having as little impact as possible on children’s health. At the same time, Gavi continues to fundraise,” the spokesperson said.

The organization will continue to support countries in the process of launching HPV vaccination programs, some using remaining 2025 funds, and those now doing routine HPV vaccination, like Nigeria. As girls there reach their 9th birthdays, they’ll be able to get Gavi-supplied vaccines.

Those include two more of Maina Modu’s children. Modu retired from his immunization officer job last month at age 56 but continues to campaign for cervical cancer vaccination, sharing his family’s story to encourage members of his community to vaccinate their daughters.

“Cervical cancer is a very dangerous and killer disease, and I learned that from my late wife,” he said. “That’s what makes me take it upon myself to make sure that I immunize them and ask others to emulate this.”

Another of Maina Modu’s daughters turns 9 in January. He plans to take her straight to their local health clinic for her HPV vaccine.

Author: Staff Writer | Courtesy of “Forbes” | Edited for WTFwire.com | SOURCE: CNN News

: 95